Chapter 10 - Parenting

Functions of Parents

"No matter what happens in this life or the next, I will always be his mother."

I heard that statement from a 56-year-old mother who lost her son to a drunk-driving-related accident. She is absolutely right that once a person becomes a parent, they are forever a parent. Parenting is the process of nurturing, caring for, socializing, and preparing one's children for their eventual adult roles. Parenting is a universal family experience that spans across the history of the human family and across every culture in the world.

Newborns are not born human -- at least not in the social or emotional sense of being human. They have to learn all the nuances of proper behavior, how to meet expectations, and everything else needed to become a member of society. A newborn in the presence of others, interacting with family and friends, typically acquires their needed socialization by the time they reach young adulthood. (Not all children are raised. SOURCE)

Parents serve many functions that play a crucial role in the society's endurance and success at many levels. Parents function as caregivers to the children in their families and thereby provide the next generation of adults. They protect, feed, and provide personal care for their children from birth through adulthood.

Parents function as agents of socialization for their children. Socialization is the process by which people learn characteristics of their group's norms, values, attitudes, and behaviors. From the first moments of life, children begin a process of socialization wherein parents, family, and friends establish an infant's Social Construction of Reality, which is what people define as real because of their background assumptions and life experiences with others. An average U.S. child's social construction of reality includes knowledge that he or she belongs, can depend on others to meet his or her needs, and has privileges and obligations that accompany membership in their family and community.

For the average U.S. child, it's safe to say that the most important socialization takes place early in life. Primary socialization typically begins at birth and moves forward until the beginning of the school years. Primary Socialization includes all the ways the newborn is molded into a social being capable of interacting in and meeting the expectations of society. Most primary socialization is facilitated by the family, friends, day care, and to a certain degree various forms of media.

Parents function as teachers from birth to grave. They teach hygiene skills, manners, exercise, work, entertainment, sleep, eating patterns, study skills, dating, marriage, parenting skills, etc. Parents teach their children at every age and mentor them through example and actions into successful roles of their own.

Parents function as the guardians of their children's lives. Twenty-four hours per day, seven days per week, 365 days a year until the child is independent, parents protect, advise, manage and support their child. They select schools, medical care, teams, daycare, and a myriad of other services for their children. The law considers the parents to be simultaneously accountable for the nature of their parenting efforts and legally entitled to rights and privileges that support and protect them. Parents are not at liberty to treat their children beyond the bounds of state and local laws. But, within those laws they have tremendous freedoms to parent according to their conscience and values.

Parents function as mediators between their children and the community at large. They act as the adult decision-maker in many matters for their children. They also act in defense of their children if misbehaviors are an issue in the community, schools, and other organizations. They act in the role of advocacy to ensure the best opportunities for their child.

Over the last few decades, nearly 4 million live births were recorded in the United States per year. About 40 percent of those are first births to a mother. Most babies are born to younger mothers. About 51 percent of all births in the U.S. are to mothers ages 15-29. (Retrieved 4 June 2014 SOURCE , Table 92: Women Who Had a Child Last Year By Age: 1990 to 2010.)

One of the more recent trends in the U.S. over the last three decades has been the increasing proportion of births to unmarried women, which is about 40-43 percent of all U.S. births. Nearly two out of three of those unmarried births are to white mothers. (Retrieved 4 June 2014 from SOURCE, Table 92: Births to unmarried Women by Race, Hispanic Origin, and Age of Mother: 1990 to 2010).

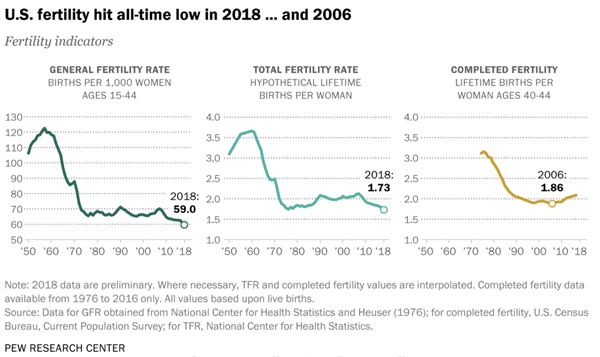

Would it surprise you to discover that in the U.S. fewer babies are being born per mother in recent years? Our Major demographic rates clearly show this pattern of declining births in multiple ways. The General Fertility Rate (GFR)= number of births in a year per 1,000 women ages 15-44. Completed Fertility=the total number of children a woman had in her lifetime (typically by ages 44 or slightly thereafter. A May 2019 PewResearch Report identified how 3 powerful measures of U.S. Fertility between 1950 and 2018 indicate that the U.S. Fertility has hit an all-time low (see PewResearch Livingston, G. (2019). “Is U.S. fertility at an all-time low? Two of three measures point to yes.” Retrieved 13 July 2020 from SOURCE

Figure 1 Shows these Trends in remarkable detail indicating that the trend previously identified in Figure 6 continue persistently as of 2016. The article reports that these trends are due to a number of factors including: declining birthrates, the great recession of 2008, delayed age at marriage, long-term educational attainment, and women’s labor force participation trends. Since many women of childbearing ages have not yet reached the age of measuring their completed fertility, time will tell if all three rates confirm ongoing record low U.S. fertility rates.

Figure 1. PewResearch Graphic of GFR, TFR, and Completed Fertility of U.S Women 1950-2018

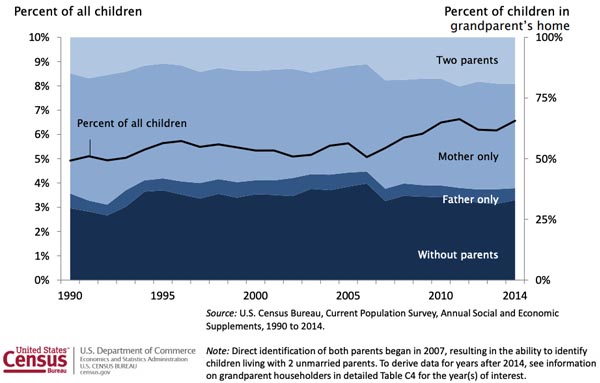

In the U.S. in 2014 there were approximately 73,692,000 children. Many were being raised in their grandparent’s home, some with a father, mother, both, or neither. Figure 2 shows the trend of which type of living arrangements U.S. children who live in the home of their grandparents experience between 1990 and 2014. This figure has percentage vales on both sides of the vertical axis. On the left, you see the percentage of all children growing up in their grandparent’s home which is about 5 percent in 1990. Look at those children in the lowest category called “Without parents.” They represent exclusively the situation where their grandparent or grandparents are providing kinship care for them. Those shows that all the research cited above and the trends between 1990 to 2014 indicate steady larger social trends of grandparents providing kinship care.

Figure 2. Presence of parents for children living in the home of a grandparent

In Chapter 1 of this textbook where we spoke of “instability” in the lives of children, we can see a critical element of U.S. parenting that needs to be discussed a bit more. Traditionally, most couples waited until marriage before having sexual intercourse. Back then, there was little to no effective birth control, so a pregnancy almost always followed unprotected sexual intercourse. Andrew Cherlin (2010) pointed out that it was the Baby Boomers who set the cultural nor that took the pattern of sexual intercourse only after marriage and extended it to sexual relations before and during marriage, after a divorce, before and during remarriage, and in the less common scenario beyond the marriage and/or remarriage sexual relationship with other partners Cherlin, A. (2010) “The Marriage Go Round: The State of Marriage and the Family in America Today” available in print or e-book form, Vintage Pub. 1st Ed ISBN 978-0307386380).

Childhood instability=is the frequent change in household and marital/relationship status of parents over the course of the first 18 years of a child’s life. It can include any or all of the following: a child born to single, cohabiting, or married parent/s; a child who experiences parents’ divorce, separation, breakup of relationship, or remarriage or repairing of cohabiting parent/s; a child who loses parent/s to incarceration, drug addiction, or death; and a child who enters the state’s foster care system (just to name some of the more common scenarios).

Cherlin’s book provides extensive insight and research to quantify the changes in the larger social and cultural levels of families in the United States over the last century leading up to the publishing of his 2010 book. One of the major claims he makes is that a shift in U.S. individualism has included only the individual now. Whereas in past decades “rugged individualism” with a heavy focus on collectivism (other focused) was courageous and allowed families to build in less inhabited parts of the country, but also focus specifically more on “individualism” as it included: me and my family.” By 2010 a huge shift in individualism had gradually shifted away from “me and my family” toward simply “self-fulfillment of me” as each individual takes care of their own individual life goals and pursuits and adventures.

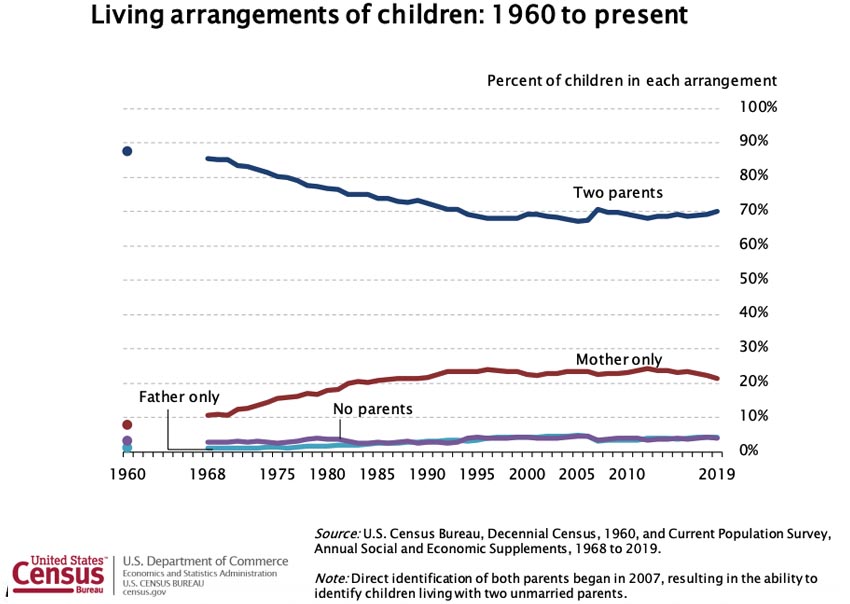

Cherlin shows (with exceptional research data to back up his assertions) how highly we in the U.S. truly value marriage, but also clearly shows how the individual “me-only” value that permeates Baby Boomer, Gens: X, Y, and now Z, collides with that high value of marriage in such a way that it leads to many of the trends we have already established in this textbook and that exists outside the scope of this textbook in international and historical data analysis. The U.S. Census Bureau often publishes trends based on their many ongoing annual surveys and on decennial census data. Figure 3 shows the living arrangements of U.S. children between 1960 and 2019. The percentage of children living with two parents (Married and Cohabiting combined) declined from about 88 percent in 1960 down to around 70 percent in 2019. In 1960 most children who did live with married parents lived with their biological or adoptive parents with only a few who had been through their parents’ divorce, remarriage, and because of WWII remarriage after widowhood. In 2019, Many of the children in “two parent homes” have instable childhoods before the remarriage ever occurs (because of the larger social and personal trend of the “Marriage Go Round”).

Figure 3. Living Arrangements* of U.S. Children between 1960 and 2019

Finally, Figure 4 adds one more crucial dimension to the instability of U.S. children which is living in poverty which shows the 29.5 million living in unmarried homes (40%) and the 44.2 million who lived in married homes (60%) in 2018 and the percentage of each subcategories that lived in poverty. The subcategories are listed in descending order with the highest percent in poverty nearest the top of each list. In the right hand column of children living with married parents, we see the overall trend of children living in married homes with their original biological or adoptive parents (who were still in their first marriage) had the overall lowest percent living in poverty (8.2%) followed closely by children in homes with remarried parents (11.3%).

The subcategories in the left hand column were for children living in unmarried homes. A quick overview shows a clear gender trend with the lowest unmarried home-poverty rates to be found in homes with single fathers (16.0%) and cohabiting fathers (18.6%). The levels of poverty increase as you keep reading toward the top of the list with levels of poverty in the following types of homes being: Grandparent (24.2%); Bio-parent and Cohabitating step-parent (28.3%); single mother (37.3%); other than grandparent relatives (39.3%); cohabiting biological parents (41.6%); cohabiting mother (42.2%); “Other circumstances (60.5%); with non-relatives (96.6%); and with those children in formal foster care (100%). Foster Care Programs consider children to be “wards of state” and provide complete welfare support for the foster care givers, even if the caregivers are not themselves living in poverty. An entire book could be written on why these levels of poverty are so much higher for unmarried parent homes. But, for this online textbook we will point to the larger social trends of recording higher: cohabiting, divorce, single mothering, divorcing, drug and substance addiction, crime participation and incarceration levels among the less educated poor than among the more educated middle and upper class. Thus, the instability of children that continues as results of the unique “Marriage Go Round” actions of parents in the U.S. is compounded by the experience of poverty.

Figure 4. U.S. Children (N=73,740,000): 2018* with Unmarried Homes (40%) & Married Homes (60%) with (% Living in poverty)

Childhood Dependence

The goal of parents from a developmental perspective is ideally to raise independent, capable, and self-directed adults who can succeed in their own familial and non-familial roles in society. Generally speaking, a child's independence is very low until adolescence. Teens exert their independence in a process called individuation. Individuation is the process of separating oneself, one's identity, and one's dependence on others, especially on parents. Children begin separating from parents in their second year, and gradual efforts at independence are visible as children master certain self-care processes during childhood. Table 1 shows the levels of dependence and a child's own ability to nurture others over certain stages of the life course.

Table 1. Children's Dependence and Their Ability to Nurture Others Over Certain Life Course Stages

| Stage | Independence Levels | Ability to Nurture Others |

|---|---|---|

| Newborn | None | None |

| 1-5 | Very Low | Very Little |

| 6-12 | Functional | Low |

| 13-18 | Moderate | Moderate |

| 19-24 | Increasingly higher | Increasingly higher |

| Parenthood | High but needs support | High but needs support |

Parenting children between birth and age 18 requires a solid understanding of how a child develops and matures through childhood and into young adult roles. Psychologists have studied child development for years. Jean Piaget (pronounced pee-ah-JAY), Sigmund Freud, Eric Erickson, John B. Watson, George Herbert Mead, Charles Cooley (the latter are sociologists), and others have developed theories that guide crucial research on children and how they develop. Since we can't cover them in detail, let's discuss a few core ideas that can guide parents and their efforts.

Newborns to 5-year-olds have little to no independence. In other words, left alone in the wilderness, most could not survive. In a home with an adult caregiver, most 0- to 5-year-olds can learn to take care of some of their own needs. They desire independence but do not yet have the thinking, muscle movement, or growth in place for it. Most have little to offer in terms of real nurturing, yet many develop nurturance in their play activities.

The children in the 6- to 12-year-old group are growing physically and developing emotionally and intellectually. They become functional in their independence and if called upon can assist parents and others with various tasks. They develop the ability to provide the caregiving of younger children, but they lack the reasoning skills required to nurture to any degree resembling the adult level of nurturing.

In the 13- to 18-year-old group abstract reasoning skills begin and children grow into complex reasoning, synthesis of related ideas, and emotional complexity. Most teens could survive if no longer under the care of an adult caregiver, but it would be difficult. They can nurture others to some degree. Generally speaking, due to hormonal fluctuations their emotional nature is volatile and extreme in terms of highs and lows.

Reading some of the details of these three age categories, you begin to see that the same parenting strategies would not work very well for each of the groups of ages discussed above. On top of that, individual children -- even within the same family -- vary on which parenting approach is most effective.

Once children attain the age of young adulthood, leave home, and/or completely individuate, they enter a role of being independent while perpetually dependent to some degree. Young adults in this generation continue to depend heavily on their parents for advice, resources, money, food, and other forms of support. Their independence would most accurately be described as increasingly higher as they prepare for their own adult roles. Their ability to nurture emotionally and in other ways is increasingly higher as well.

Once children become parents on their own, they enter the roles of mother and father and join the ranks of tens of billions of parents who've lived before them and fundamentally attempted to do about the same things for their children. Young parents often see their own parents as a tremendous resource of experience and knowledge. Studies show that young parents adjust better when they have access to support from friends and family. Simply put, they benefit a great deal from having a listening ear and someone to share words of parental wisdom. These adults are independent and can nurture, especially with support.

Finding the Balance Between Control and Freedom

With all of this variety and diversity of development and growth, how can parents plan for and properly perform their parenting roles? The answer is to find a handful of parenting paradigms and approaches that will work with children. There are a few core approaches that originate from the classical and contemporary parenting scientists. Figure 5 shows one useful model that I developed from many research studies and from a number of parenting paradigms and which can lead to an ideal outcome of having raised children who are independent co-adults (defined below).

Figure 5. An Ideal Parenting Approach for the First 20 Years of Life

Many families have a tradition of just surviving the traumas, addictions, heartaches, and tragedies that preceded them in their upbringing. The base of this model presents the two strategies of first, urging individuation, and second, avoiding enmeshment with your children. Individuation is the process by which children become their own persons and learn to identify themselves as distinct individuals with unique tastes, desires, talents, and values. Individuated children can distinguish between the consequences of their own behaviors and consequences of others.

An individuated child develops his or her own taste in music, food, politics, etc. These children see their family as one among many social groups they belong to (albeit one of the more significant ones). An example might include although ashamed of a drug-addicted brother, an individuated child fully realizes that the brother has made his own choices and must live with them and that the brother's behavior may be embarrassing at times but does not reflect the nature of the rest of the family members. Individuated children have also developed enough independence to strike out on their own and assume their own adult roles.

It is very wise to avoid relationship patterns of enmeshment. Enmeshment between parents and children occurs when they weave their identities so tightly around one another that it renders them both incapable of functioning independently. Many parents create this pattern in their relationship when they assume that their child is an extension of themselves, not much unlike the "Mini Me" in the movie Goldfinger. Enmeshed parent-child relationships often have very weak boundaries and unhealthy interdependence that lingers into adulthood. Think of spaghetti noodles over-boiled to the point that they form one large gooey mass of paste. They would be considered enmeshed or entangled with one another.

An example of this came to my attention when one of my students complained that her parents had maxed out her credit cards for a vacation cruise. She couldn't apply for a student loan after that because of her credit score. Another student's mother insisted on having her way in his marriage, including deciding on birth control, class scheduling, and even how his wife should breast feed the "proper" way.

Parents who allow their children to make most of their own choices give their children opportunities for growth and development that contribute to high individuation and low enmeshment. Examples might include, "Which T-shirt do you want to wear for school today? What would you like to drink with your dinner? Or, let's sit down together and set some guidelines for how to be safe on a date." Children of all ages respond well to parental attempts to promote independence, individuation, and self-sufficiency. They may not understand it while the children are young, but parents who allow the individuality of their children to develop and who avoid seeing and treating their children as simply extensions of themselves empower their children to move out on their own and accept adult roles.

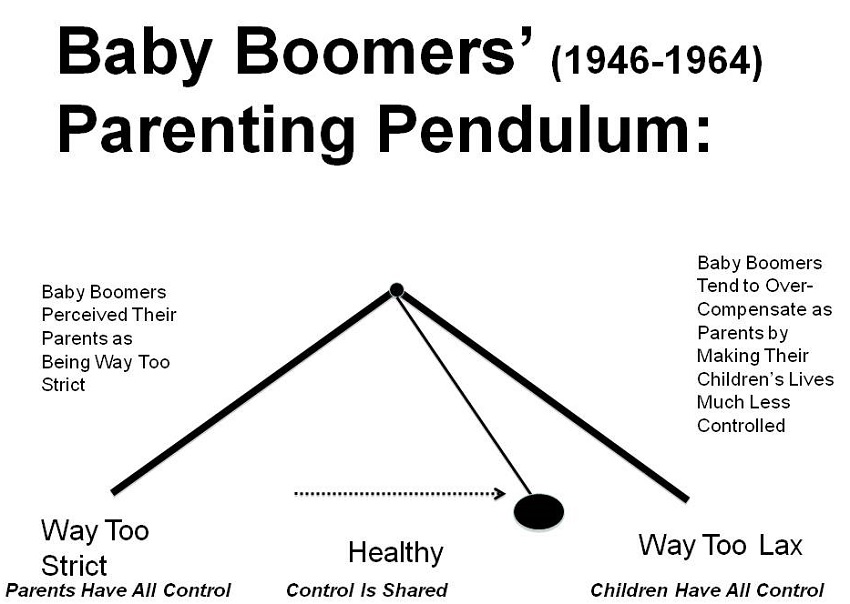

Many studies have focused on how much support and how much control children should be given by their parents. Generally speaking, parents with high levels of support for children and their interests will find the most favorable outcomes. If parents want their children to grow up healthy, accomplish individual goals, become contributing members of society and avoid delinquency, then supporting those children in as many ways as possible is a good idea. But support alone is not enough. Children need guidance and control. They need their parents to set healthy limits and enforce consequences when these limits are exceeded. They need parents to be involved in their lives enough to be very specific about limitations and rules. They need parents to be in charge. There is a generational effect that relates to this support and control approach. Figure 6 shows the trends that transpired for Baby Boomers and their children.

Figure 6. The Baby Boomer Parenting Pendulum

Baby Boomers were born in the years 1946-1964. Their parents were of the old school "spare the rod, spoil the child" or "you live in my house, you live by my rules" paradigms. These parents were very strict and rigid about parental authority reigning supreme. Parents of Baby Boomers took and had nearly all the control. Funny, isn't it, that the Hippie rebellion came from this generation of over-controlling parents. Children typically rebel when there is something to rebel against, especially against a strict display of authority. It's much easier to rebel against rigid parents than democratic ones. When a moderate measure of authority is presented to them, they often have minimal needs to rebel.

The middle of the continuum is the healthy zone, where control is shared between the authority figure (parents) and the developing members of the family (children). Healthy parents seek for and apply children's input. Vacation plans, home remodeling, even cars and colors of cars are often decided upon in family meetings or gatherings. Healthy parents tend to have enough confidence in themselves to yield some of the control to children -- but not all of it.

This brings us back to the Baby Boomers. They collectively held strong beliefs against repeating the harshness placed upon them by their parents. Many made the mistake of under-controlling their children. They let their children self-discover their own paths in life. Many Baby Boomers, as parents themselves, felt remorse when their children made serious mistakes in life. Some of these mistakes might have been avoided by an increase in control. You see, children with too lax of parents often act out just to test their parents' interest in and devotion to them. Many in-patient treatment facilities are filled with the children of under-controlling Baby Boomer parents.

Children raised in homes with highly supportive and moderately controlling parents grow up and become contributing adult members of their own families and communities. Our freedom to choose must never be taken or limited by threats or coercion. By the same token, parents make a huge mistake by parenting with a "hands-off" attitude toward their children. The research on parenting styles indicates that parents must be the authority figures in the home, they must take a stand, and they also must allow their children to negotiate their own will amidst all of the worldly distractions and choices they are faced with every day.

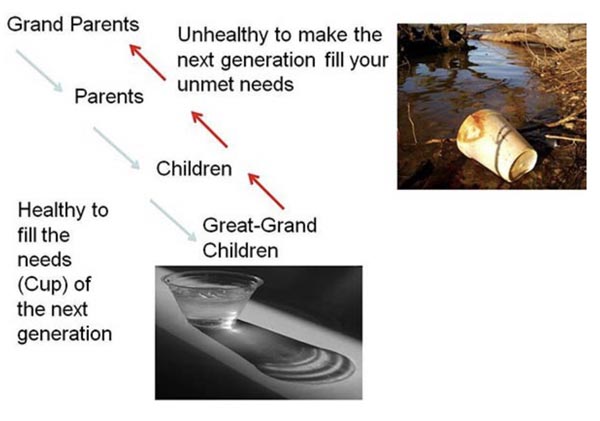

Figure 7a shows another issue related to high support and moderate control-caring for the next generation.

Figure 7a. The Healthy Way to Nurture Down the Generational Lines: Fill the Cups of Your Children and Their Children

Many parents grew up under circumstances limited by unmet emotional, financial, or social needs. Where abuse and addiction were involved, they too often grew up as caregivers rather than as dependent children. When this happens, the children grow into adulthood with childhood deficiencies (see Abraham Maslow's Pyramid of Hierarchy of Needs).Thus, as adults, these individuals enter the ranks of parenthood looking to have their childhood needs be met by their children. This can create a parenting legacy where the children, grandchildren, and even great grandchildren are nurturers and caregivers to their parents, grandparents, and even great-grandparents (look at the red arrows in Figure 4). Even if a parent was not raised in a highly supportive and moderately controlling home, and even if he or she has unmet childhood needs, the essential task at hand is to provide for and nurture their own children and grandchildren (see blue arrows in Figure 4).

The challenge is to break the chain of counter-caregiving. Parents who seek professional counseling often learn that unmet childhood needs are like water long-passed under the bridge, which cannot ever truly be recaptured. However, their approach to filling their children's needs and supporting and controlling in a healthy manner can actually provide some healing for the parent and ultimately reverse the unhealthy pattern or tradition

.The metaphor used by one of my graduate school professors was simply, "Water flows downhill. No matter the upbringing a parent had when he or she was a child, the task at hand is to fill the cup [needs] of the next generation. Make sure and do whatever it takes to break this cycle of trying to extract water [caregiving] from younger family members who themselves are too young and inexperienced to become caregivers" (Boyd Rollins, Ph.D., "Advanced Parenting Research Lecture Notes," BYU, 1990). It's a simple metaphor, but effective enough.

Behaviorism and the Cognitive Model

The next level in the model presented above in Figure 5 is called Behaviorism. Behaviorism is a theory of learning that simply states that children will repeat behaviors that they perceive to bring a desired reward while ceasing behaviors that they perceive bring punishments. All of us (children, too) tend to maximize our rewards while minimizing our punishments. The behaviorism approach to parenting is a powerful paradigm when it comes to raising smaller children. Reasoning skills haven't developed enough in preschoolers. You understand the dangers of busy streets and traffic risks, but when you tell a small child not to play near one, they typically cannot process all the nuances of the dangers that might occur.

A four-year-old will learn better from a parent who makes him come in for 10 minutes of time-out if he forgets and goes near the street again. He may say that his ball rolled into the street and he simply retrieved it. To a small child, 10 minutes may feel like hours. This is a strong punishment to a child who wants to play. Now, it can be argued that an angry swat on the behind is also going to be perceived as a punishment. This is true. But numerous studies consistently indicate that non-spanking approaches to disciplining a child can be very effective. A 2013 ABC News poll found that about 65 percent of Americans approve of parents spanking children, but only 26 percent approve of spanking in the schools (Retrieved 4 June 2014 SOURCE).

Many parents are very aware that the state authorities will hold them accountable if they do not protect their children from danger. They also know that psychologists and others frown upon spanking. Thus, spanking has gone underground for many parents. It takes place behind closed doors. This is a big change from the 1960s and 1970s, when I grew up in Georgia. Back then you could be whipped by a belt, a small limb of a tree (switch), and wooden paddle, or another convenient object at home, at school, at church, or on the bus. It was perceived to be "for my own good." Go figure. Yes, I'm a Baby Boomer.

I know of a spanking received by my student. Her stepmother swatted her with a wooden spoon, and her father perceived it as being highly out of line. Thus it was the only spanking she ever received. When she eventually married, she was determined not to spank, so she bought a book that offered alternatives to spankings. Her husband came in one day from a long day of work and found her in tears. She had two toddlers who were misbehaving and she had spanked them each with a simple swat on their diaper. Her husband reassured her by saying that it was fine and he thought that she had done what any mother might do in her place. She agreed, but she explained that she was probably the only mother in the world who had administered the swat using the paperback book she was reading on alternatives to spanking. True story.

Spankings are common and are often used when parental frustration leads the parent to lash out. For many parents, behaviorism is a guiding strategy that focuses the parent's attention on effective parental intervention efforts that work well and often work quickly. The key in using this approach is to know your child well enough to know what he or she defines as a reward or a punishment. Some children are sensitive to parental criticism and will respond well to a disappointed look or tone of voice.

Other children respond better to giving or withdrawing privileges (Xbox, cellphone, TV, or play time with friends). Once you get an idea of where your child stands on rewards and punishments, then you can selectively use a reward or punishment approach. I remember my daughter's kindergarten teacher, Mrs. Peterson. She told us during the first parent-teacher conference we had with her that "One Tootsie Pop as a reward is more effective than 100 spankings or scoldings." She was correct and effective with her students. Your children will probably have rewards and punishments that vary from child to child. Table 2 shows some of these to illustrate the point, although it would be impossible to list the rewards or punishments of every child in the world.

The behaviorism formula is relatively simple once you've identified your particular child's rewards and punishments. If you want a child to learn a new habit or improve on a skill, motivate them with a reward. For example, if she puts her own dirty laundry away for a week, you'll let her pick out her next outfit at the store (then really let her pick it out, no matter what you think about it). You can also add unexpected rewards. For example, you notice that your son is playing well with his little sister and you come in and praise them both with a treat for playing well together. This rewards desirable behaviors in unexpected ways and can be a powerful reinforcer for desired behaviors.

You can also withhold rewards when misbehavior occurs. For example, a child who gets an hour of video game time after his chores and homework are finished might lose his hour on a day on which he forgot to do his homework. Likewise, a grounding may be applied for other behaviors and consequences. One of my personal favorites as the father of six was to purposefully give a long grounding. After a few days, I'd offer the child a negotiated early release for improving the behavior or activity at hand.

The core of the most effective rewarding and punishing system is to connect the reward or punishment to the natural consequence of the behavior. In other words, when a teen stays out past their curfew, grounding them from their friends is the natural consequence. It helps to logically reinforce the behavior to the outcome. If you want a child to behave in a public setting, reward the child while they are behaving. Many well-meaning parents wait until the child is frustrated and misbehaving then break out the treats. When they do this, they are rewarding misbehavior with treats.

Table 2. Examples of Rewards and Punishments for Children

| Possible Rewards | Possible Punishments |

|---|---|

| Verbal approval | Verbal disapproval |

| Verbal praise | Verbal reprimands |

| Sweets | Time out (in chair, bedroom, corner) |

| Playtime, friend time | Groundings (from friends, toys, driving, etc.) |

| Special time with parents | Chores |

| Access to toys | No access to toys |

| Money/allowance | Suspended allowance, small monetary fines |

| Permission | Denial of opportunities |

| Driving, outings with friends | Withdrawal of privileges |

One of the findings about behaviorism is that it works best for younger children and should be complimented with a logical or thinking-based approached called the Cognitive model as the children get older. The Cognitive Model of parenting is an approach that applies reason and clarification to the child in a persuasive effort to get them to understand why they should behave a certain way. After age 7, children develop more and more reasoning skills. Children younger than that will try to understand, but they benefit more from short statements and behavioral rewards and punishments. Teenagers and young adults have developed abstract reasoning skills. They can think and reason complex matters and therefore can carry on conversations and present their case while understanding their parents' case.

The cognitive model is a relief for many parents who complain that behaviorism feels too much like a bribe or extortion because the parents are using that paradigm to get desired results. My answer to this concern is that when someone bribes or extorts another, they are typically doing it for selfish reasons. When parents use rewards and punishments with smaller children, the desired outcome is typically supportive of the child and the child's development and growth. It's not a bribe to help someone be a better or more mature person.

Finally, remember that children (and adults) tend to do what rewards them while avoiding what punishes them. If they typically speed to work without getting caught, they continue to speed. If they do get caught and accumulated points against their license, say with the threat of losing it if they got one more ticket, then slowing down to avoid the punishment becomes more appealing. We tend to avoid repeating behaviors that punish us in undesirable ways.

Would that any parenting paradigm worked for every child in every case, but none does. Behaviorism and cognitive approaches fail with some children, especially when their emotions override their reason and their judgment. Teenagers have very emotional decision-making processes that often require tremendous patience from parents. Even when a child's behaviors and thinking are irrational and based more on emotional approaches, these paradigms still work better than none at all or better than simply spanking or grounding.

The next step in the model shown in Figure 2 is to assimilate children early into responsibility and eventually into their adult roles. Parents often don't want to let their children suffer. But they eventually learn that a child's failures are not a bad thing. It can be a powerful learning experience for a child to fail when trying out for a team, a play, or a job. Their mistakes inform their ability to learn and improve according to their strengths and weaknesses. There are a few parenting types that support children learning from their own efforts and a few others that are more interference in that processes.

Types of Parenting

Rescue Parents are constantly interfering with their children's activities. They continuously help with homework (or do it for the child), seek special favors for their children from teachers and/or coaches, rush in before the child can fail to extract the child from the risk of failing, or make sure the child never has to face any consequences for his or her actions. Rescue parents undermine their child's self-worth by removing their child from any risk of failure in the pursuit of successes. This makes the child feel incapable of doing things on his or her own. Rescue parents raise children who are dependent, non-individuated, and often enmeshed.

Dominating Parents over-control and coerce their children. They typically demand compliance and are harsh and overly strict in their punishments. They continuously force their children to dress and act as the parent desires. They force their children's choices of friends, hobbies, and interests. They also use humiliation and shame to make the child comply. These dominating parents make the children prisoners of their control and dependent upon the parent or someone who eventually replaces the parent (such as a dominating spouse).

Mentoring Parents tend to negotiate and share control with their children. They typically let the small things be decided by the child (clothing, class schedules, and hobbies). They also tend to set guidelines and negotiate with their children on how to proceed on various important matters (minimum age to date, when and what type of cellphone to acquire, and when to get a driver's license). They often give the child choices. For example, a parent might say, "I can't afford to get you a car of your own, but if you don't mind too much driving the old family van, I'll share the insurance expenses with you." Or for a younger child, the parent might say, "You can wear your T-shirt or tank top, but you can't go shirtless to the park because the sun might harm your skin."

Figure 7b shows a photo montage of parents and children. As you look at the photos of parents and their children, think about how they represent the myriad opportunities for children to take on and accept responsibilities. Parents find that even early in the pre-school years, children can take on small chores and tasks around the house. If doing chores is defined as positive and rewarding, children can learn to work side by side with their parents in house and yard work. Such skills are invaluable in our day. Employers struggle to find teens and young adults who have experience working and fulfilling assigned tasks adequately.

Generally speaking, when parents and children work together on mundane tasks, there is a much higher likelihood of establishing a bond and an emotional connection than if family members are just watching TV or playing on the computer. Much research has shown that, with most women being in the labor force, men and children have more opportunities than ever before to perform house and yard work. Doing work together as parents and children can be a very bonding and growing experience for both.

I often ask my students this question, "How many of you were asked to do more than kitchen work or house cleaning by your parents when you were growing up?" Over the last 20 years, most of my students have cleaned their room and done kitchen work as their main work experiences. Every once in a while a child from a farm background wows the other students with the types of difficult and complex work they did from about age five on (this is in part why farming is so dangerous to children). Many of my students work part-time to put themselves through college. Those who already established good working relationships and the ability to follow through have a better work experience.

Figure 7b. Photo Montage of Parents and Children

Parents trying to raise their children to be responsible co-adults may need to know what being a co-adult child means. Co-adulthood is the status children attain when they are independent, capable of fulfilling responsibilities and roles, and confident in their own identities as emerging adults. The opposite of co-adulthood is simply dependent adult children, many of whom are enmeshed with their parents and other family members.

A co-adult is independent. But that does not imply that she or he is no longer in need of support and guidance. Just the opposite is true. Many studies of college-aged young adults show a continuing reliance on their parents clear until their mid to late twenties. Psychologists will tell you that their studies suggest that the U.S. young adult has a fully mature brain around the mid to late twenties.

One thing needs to be said about parenting; parents are not the only ones who socialize another family member. Studies have shown that children socialize parents as well. I joke with my wife about how she and I debated as newlyweds about someday saving up and buying a pickup truck or a Ford Mustang. When we found out that we were expecting our first child, we caught ourselves one day in a Dodge sales lot looking at the newly invented minivans (early 1980s). Wow! You could have tipped us over with a feather when we both realized how our tastes had changed based on the expectation of a child.

Parents go through dramatic changes in anticipation of and accommodation to a newborn. Newborns come with 24/7, 365-days-a-year constant needs. Sure, parents buy the bottles, diapers, toys, etc. But, the baby sets the standards for how they like to be fed and when. The baby sets the sleep patterns (especially in the first six months). The baby conditions the parents to hold them, play with them, and interact with them on their own terms.

Sure parents socialize the baby at the same time. But the baby, with very little conscious effort, sets the rules of much of the caregiving game because he or she cries when unhappy or when needs are unmet and smiles and giggles when things turn out as he or she wants them to be. Thus, the parents are rewarded by giggles and smiles while being punished by crying and tears. It becomes easy to acknowledge that parents who want to provide the best care for their children are indeed socialized by each child to meet that child's needs in a certain way.

When the child socializes the parent, it is not planned at first. It is just their way of surviving. When the parent socializes the child, much of the parent's own upbringing, own understandings about what a parent is "supposed to do," and knowledge of what the experts are saying comes into play. This is why it is so important for parents to carefully consider how they socialize the child's sense of self-worth.

Self-worth vs. Shame

Self-worth is the feeling of acceptance a child has about his or her own strengths and weaknesses, desirable and undesirable traits, and value as an individual. To sociologists, self-esteem or the high or low appraisal is not as important today as it was thought to have been 20 years ago. I have urged my students for over two decades to teach their children to value themselves and acknowledge the simple truth that no one is perfect, that no one is good at everything, and that each child has the opportunity to discover his or her own uniqueness. There is innate value in being unique and an individual. Parents are in a prime position to teach their children to see a balance in how they value themselves.

One of the most demeaning messages sent to children from their parents is a message of shame. Shame is a feeling of being worthless, bad, broken, or flawed at an irreparable level. I once gave a seminar to students on shame. I walked in with a fresh bottle of never-opened apple juice and asked them if anyone would drink this if I gave it to them. Most raised their hands to indicate they would. I then defined shame and asked them to check the bottom of their shoes for dirt, twigs, or small stones. I then opened the apple juice bottle and dumped all that debris from their shoes into the bottle. "Who would drink this now?" I asked. For some reason none of them would.

I then poured the apple juice into a glass and left all the debris in the bottom of the bottle with half the juice. Still no one would drink it. "Why?" I asked. "Because the juice is ruined and the very thought of knowing what was in it makes it worthless." One student responded. "Exactly!" I explained. "Some parents raise their children to believe that they are as worthless and ruined as was the apple juice and that nothing could be done to fix them." My point is that many parents today raise their own children in the same shame-based manner that their parents used on them. Shaming children will never yield the positive outcomes parents want in their children.

Shame is at the core of every single addiction, be it alcohol or drugs, TV or gambling, eating or shopping. Addiction is a natural expectation for people who define themselves as permanently broken or flawed. Recovery programs focus specifically on how to help the addicts accept themselves in a broken state (like most non-shamed people already do).

Shame is not the same as guilt. Guilt is a feeling of remorse for doing something wrong or not having done what one should have done. Guilt may be healthy. Shame rarely is. The generation that raised the Baby Boomers used shame the same way they used a belt. It was an emotional tool devised to control and sometimes break the will of a child so that he or she would conform to the parent's will. Many of those Baby Boomers use shame today on their children and grandchildren. Shaming a child teaches them to accept their permanently broken status and give up hope on finding the joy of their own uniqueness’s and talents.

Parents don't have to use shame, even if their parents did it to them. Parents are the significant others of their children. Significant others are those other people whose evaluation of the individual are important and regularly considered during interactions. Parents are in a prime position to teach healthy self-worth or toxic shame and worthlessness. Especially for their preschool children, parents teach their children how to see value in themselves and to see balance in how they find out what they are good at in life.

Parents avoiding shame teach their children how to learn from failures and mistakes. They teach them how to be patient and work hard at their goals. When the outcome goes in an undesirable way, these parents console their child and reinforce that child's uniqueness and value as an individual. These parents teach their children not to draw hasty conclusions too early in life. When the children have tried and tested their talents and limits enough and launch out on their own, they can take not only a positive evaluation of themselves into their adult roles but also a process of balancing their strengths and weaknesses in the big picture of their lives.

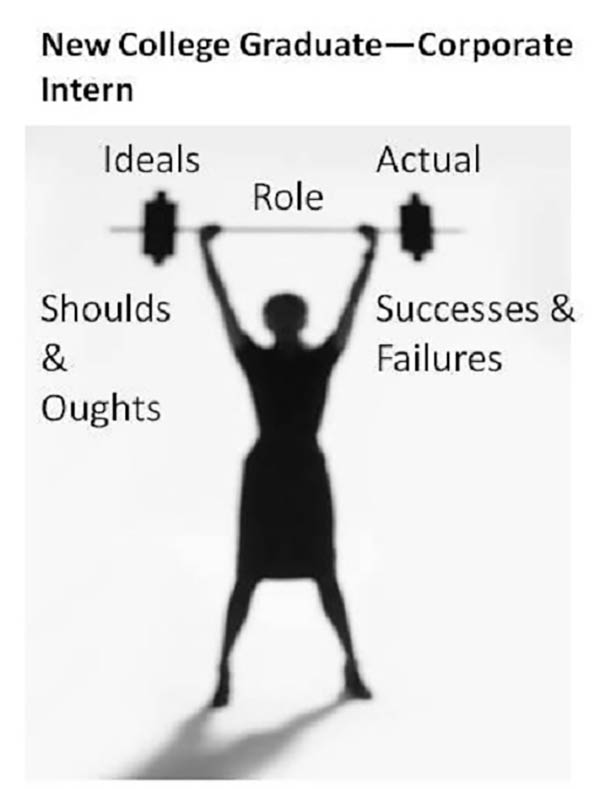

The process leading up to a healthy self-worth is easy to grasp. I've taught my students for decades to think of how they get feedback from others and watch others to get an idea of their expectations in a given role as though they were a weight lifter. Look at Figure 8 to see a metaphor on how we measure our self-worth by weighing our ideal expectations against our real or actual performance.

Figure 8. How Our Self-Worth Is Weighed in Ideal and Actual Terms

The key to understanding self-concept is to understand that balanced self-concept works the same way as balanced weights. Ever try to lift a weight set with 30 pounds on one side and only 20 pounds on the other? Please don't!

The same can be said of those who try to balance too high of an "Ideal" expectation in a role, because they're most likely to perform less than expected in their "Actual" performance in this role. Again, balance between "Ideal" and "Actual" is crucial. In this example, imagine that you are looking at the self-concept formed by a young female college graduate. She has been accepted into a prestigious corporate internship role and has actually been labeled the "Intern."

If this young professional woman was raised to be fair to herself and others in seeing the balance of her worth in terms of reasonable "Shoulds and oughts," she will be more accurate in learning from her successes and failures rather than simply chalking them up as more evidence of her core worthlessness (rocks in the apple juice). The goal is to help children learn to set reasonable goals and see their own efforts as objectively as possible.

As parents, your definition of self-worth will shine on your children in direct and indirect ways. They will see how you keep the balance or don't. Make a concerted effort to value your children. Express that value to them often (some suggest that you should express it daily). Make a concerted effort to console them in their grief when they feel they might have let themselves or others down. Then teach them how to see their worth in terms of being good at some things (like most) and not so good at others (like most).

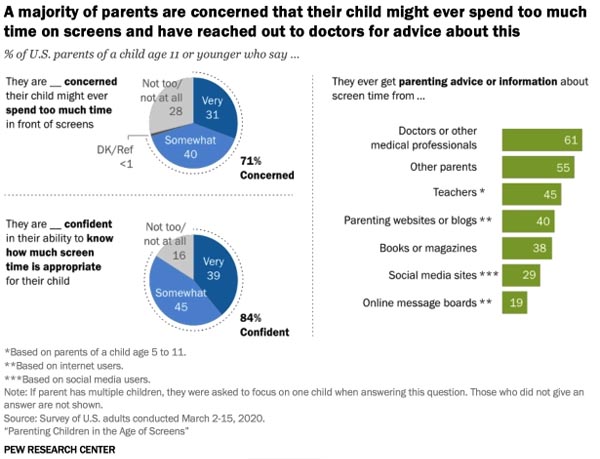

As we get closure on the sociology of parenting let’s consider the question “is parenting harder for parents today than it was for parents of past generations? What do you think? PewResearch conducts extensive surveys in the U.S. and almost every other country of the world. They asked a scientific sample of U.S. parents a series of survey questions to find out if parents today think they have it harder than previous ones (see PewResearch (2020)“Pew Research Center, July 2020, “Parenting Children in the Age of Screens” downloaded pdf on 4 August 2020 from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/07/28/parenting-children-in-the-age-of-screens/ ). They have an ongoing panel survey of citizens of the U.S. called “American Trends Panel” (see the scientific specifications at https://www.pewresearch.org/methods/u-s-survey-research/american-trends-panel/ From this survey they considered responses from 3,640 U.S. parents with children under the age of 17. They found that exactly two-thirds (66%) of their respondents felt that parenting was harder for them today!

Figure 9 shows the details of how they responded to questions about parents who worry about “screentime (screentime includes: smart phones; tablets; computers; TVs; video games etc.). Most of the parents had this concern at some level (71%) and many had sought input from professionals and outside resources to better understand just how much might be too much. Also interesting is that 84 percent felt confident to know how much screentime was appropriate for their child. Other parental concerns included: social media concerns; changing morals, violence, and drugs; tech exposure to unhealthy behaviors; both parents working for pay; and other interesting concerns.

Figure 9. PewResearch Results of U.S. Parents who are Worried about “Too Much” Screentime for their Children

PewResearch also identified a social media-based newer component of parenting called “Sharenting”. Sharenting =the practice of posting videos, stories, photos, and other details of the child’s life on social media (see NYTimes editorial by Kamenetz, A. (5 June 2019 at https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/05/opinion/children-internet-privacy.html ). PewResearch reported that 81% of these parents had been sharenting. They found some interesting demographic patterns of having practiced sharenting. For example: 89 percent of women and only 71 percent of mend did this; younger ages 18-29 (Gen Y & Gen Z parents) did it at 87%; Gen X parents at 83 percent; and the 50 and older generation (Gen X, Baby Boom, and Silent Generation) did it only at 72%.

Sharenting is common among current parents of all ages but especially among current parents of younger ages. One might wonder what parents in the year 2050 might be doing to best raise their children and how technology is part of those parenting efforts as it is today. Perhaps those parents will look back and say something like, “parents had it so easy back in 2020…”

We’ve included five self-assessments to help you better understand your own parenting experiences both growing up and as a parent in your own right.

Parenting Quiz

Please circle the appropriate answers which apply to you for each item below.

| 1. Do you preside as the parent in your home? | Yes | No |

| 2. Do you facilitate your child=s skills in making choices? | Yes | No |

| 3. Do you often connect the consequences of your child=s behavior to his or her actions? | Yes | No |

| 4. Do you know what your child=s needs and desires really are? | Yes | No |

| 5. Could you make a list of the top 5 needs and top 5 wants of your child? | Yes | No |

| 6. Do you often direct your child to behave in a healthy and responsible manner by connecting satisfying consequences to his or her needs? | Yes | No |

| 7. Do you often reward positive and healthy behaviors in your child? | Yes | No |

| 8. Do you often penalize negative and unhealthy behaviors in your child? | Yes | No |

| 9. Do you often make positive and healthy behaviors an appealing choice for your child? | Yes | No |

| 10. Do you often make negative and unhealthy behaviors appear to be too costly to your child? | Yes | No |

| 11. Do you allow your child to experience something unpleasant (not dangerous) as a motivator to behave? | Yes | No |

| 12. Do you arrange your child=s environment in such a way as to maximize his or her opportunities to behave properly? | Yes | No |

| 13. Do you often apply negatives when you want to decrease misbehaviors? | Yes | No |

| 14. Do you often remove something pleasant from your child in order to decrease misbehaviors? | Yes | No |

| 15. Do you often arrange your child=s environment so that misbehaviors cannot occur? | Yes | No |

| 16. Do you often remove the payoff when your child misbehaves? | Yes | No |

| 17. Do you often distract your child when he or she is fixated on asking for something you do not want him/her to have? | Yes | No |

| 18. Do you often provide more desirable alternatives for your child when he/she wants to do something you do not want him/her to do? | Yes | No |

| 19. Do you sometimes satiate your child with something he/she desires (not dangerous) in order to make them become sick of it? | Yes | No |

| 20. Do you agree that all misbehaviors can be changed if the proper approach is used? | Yes | No |

| 21. Are you often capable of seeing how your child=s misbehavior is paying off? | Yes | No |

| 22. Are you often capable of discerning when your child is trying to shock you? | Yes | No |

| 23. Do you have a plan for managing your child=s indolence? | Yes | No |

| &24. Are you often, silent, supportive, promptive, & reflective when you listen to your child (answer yes if any apply)? | Yes | No |

| 25. Do you often avoid the use of sarcasm, punishing your child=s honesty, labeling, & jumping to conclusions (answer yes if any apply)? | Yes | No |

| 26. Do you often postpone talking to your child about difficult issues until a time when you are both well rested and clear minded? | Yes | No |

| 27. Do you often have unconditional love for your child? | Yes | No |

| 28. Do you often have resultant love for your child? | Yes | No |

| 29. Do you often let your children make their own mistakes and assume responsibility for the consequences? | Yes | No |

| 30. Overall do your positives far out way your negatives when the daily interactions with your child are considered? | Yes | No |

Key: Give yourself 1 point for each AYes@ answer. Add up your total points. This assessment is scored toward excellent parenting patterns. A higher score indicates better parenting skills.

Try not to get discouraged if your score is lower than you wished it to be. Parents are usually ill equipped for parenting when they first start out and most improve significantly with time, trial, and wisdom gained from mistakes. Even parents with excellent scores on the quiz can improve their habits and skills. The most important strategy to remember (for parents who want to improve) is the strategy of developing a paradigm or framework from which to parent. Find out what works best for you and your family. Try it as you apply it and realize up front that nobody is perfect and nobody expects parents to perfectly parent.

The quiz you took above is from the Behaviorism paradigm. You can learn more about it from Paul Robinson and Leo Hall=s book, Answers: a parents= guidebook for solving problems. (1993) Lion house press, Canby Oregon. It works especially well with younger children but not so well with older teenagers and adults. Dr. Robinson, like most experts provides scientifically and practically proven guidelines for parents. Take them as guidelines not as mandates. Use those guidelines which work best for you.

Notes:

© 2014 Ron J. Hammond, All Rights Reserved

How Has Parenthood Changed You?

Most researchers have expended considerable resources in the study of the effects of parents on children. Very few studies in comparison have studied the effect of children (parenting) on parents. This exercise will allow you as a parent to observe some of the changes which have taken place in your life. First try to remember how things were before you became a parent. Once you have completed the before section go to the after child/ren section and complete it. Next, briefly summarize your evaluation of these changes.

| Area of your Life | Before Child/ren | After Child/ren | Your Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Physical Health | |||

| Figure/Build | |||

| Fitness | |||

| Frequency of Illnesses | |||

| Risks of Accidents | |||

| Daily Nutrition | |||

| Overall Happiness | |||

| Family Satisfaction | |||

| Career Satisfaction | |||

| Marital Satisfaction | |||

| Social Life Satisfaction | |||

| Spiritual Satisfaction | |||

| Educational Satisfaction | |||

| Intimacy Satisfaction | |||

| Type of Vehicle You Desire | |||

| Type of Recreation You Desire | |||

| Daily Levels of Stress | |||

| Type of Music You Prefer | |||

| How You Unwind or Relax | |||

| Type of Employment Which Fits Your Needs | |||

| Relationship with Parents | |||

| Relationship with In-laws | |||

| Connection to Community | |||

| Connection to Religion | |||

| Overall Life Plans | |||

| Feelings of Control of Your Life's Course | |||

| Feeling of Adequacy as a Parent | |||

| Conservativism | |||

| Liberalism | |||

| Intellectual Interests | |||

| Casual Reading |

Consider these questions for this exercise:

- How many of the changes you observed would have occurred even if you had no children?

- Overall what is your evaluation of the effects that children have had on your life?

- If some of the areas indicated no change, do you think that change may yet occur? If so how do you feel about it?

- How will life be after your child/ren are gone? What types of adjustment will be necessary for that transition in life?

Notes:

© 2014 Ron J. Hammond, All Rights Reserved

Single Parenting Assessment

This assessment is specifically designed for single parents. Other parents can take it because many of the parenting principles are similar regardless of marital status. Also, if you are not a parent, it might be very insightful for you to interview a single parent using this questionnaire. Either way, wait until the assessment is completed before looking at the key. The use of the word, "children" in the questions is meant to imply one or more children.

- T/F. I have a good life

- T/F. My emotional needs are meet

- T/F. I could use more time spent in the company of adults

- T/F. I have good friendships

- T/F. I exercise regularly

- T/F. I get adequate sleep at night

- T/F. I manage stress successfully

- T/F. I am not over weight

- T/F. I look attractive

- T/F. I have a nice wardrobe of clothes

- T/F. I enjoy the place we live in

- T/F. I have my intimacy needs met

- T/F. I have enough money

- T/F. I have adequate privacy

- T/F. I pursue my hobbies

- T/F. I rarely go to bed tired

- T/F. My social life works for me

- T/F. I enjoy my extended family

- T/F. I enjoy parenting

- T/F. My children are basically unhappy

- T/F. My children do not listen to me

- T/F. My children get more of what they want from me than I am would like

- T/F. My children need another parent

- T/F. My children need more of my time

- T/F. My children take me for granted

- T/F. My children are not feed to my standards

- T/F. My children run over me sometimes

- T/F. My children drain my energies

- T/F. My children are not learning responsibilities

- T/F. My children spend too much time without me

Key:1-19=True & 20-30=False.

Score_____.

This assessment is biased toward healthy single parenting. A score of 30 means very healthy and 0 means very unhealthy single parenting. A single parent often has more responsibilities than couple parents. The first 19 questions deal with the single parent=s well being as an individual. Questions 20-30 deal with the single parent=s perception of their parenting performance by measuring outcomes of child well-being. Discuss the issues presented in each item. Which is/are the most critical? Which needs immediate attention? What can be done, given the single parent=s resources to bring about change?

© 2014 Ron J. Hammond, All Rights ReservedFatherhood Patterns Assessment

This assessment is designed to explore your impression of fatherhood. By answering the questions below, you will become familiar with the types of patterns exhibited in fathering behaviors, especially those you saw from your perspective as a child growing into adulthood. As you answer the T=True and F=False questions below, think about your own father, stepfather, grandfather, or adult male (only one role if possible) who you would consider the primary father figure in your growing up stage of life.

- T/F I could clearly tell when I had done wrong with him

- T/F The most common form of punishment was physical in nature

- T/F He would forgive my mistakes

- T/F He was never around to know if I was doing something I shouldn't do

- T/F He would forget about what I had done so I could move on

- T/F He punished me with reasonable punishments

- T/F At times, I really felt afraid of him

- T/F We always did things together

- T/F He was frequently at home in the evenings and/or weekends

- T/F He never really knew what I was going through

- T/F He knew who my friends were

- T/F He was a good provider for me

- T/F I felt protected by him

- T/F If people knew what I knew about him, they'd say he was a good father

- T/F I couldn=t really talk to him

- T/F He was there to be a part of my life events

- T/F I was satisfied with his involvement with me

- T/F I could wake him up to talk if I needed to

- T/F He would take me shopping with him

- T/F He and I played regularly together

- T/F He touched me in ways I needed

- T/F He was cool around my friends

- T/F More than once, he pulled me out of a jam

- T/F He spent his money on me

- T/F I did not learn much from him

- T/F We worked together on things

- T/F We get along well now

- T/F When I was hurt, he took care of me

- T/F He=s the kind of person I=d Like to be

- T/F If I were like him, I=d make a good parent

Key:1=T,2=F,3=T,4=F,5=T,6=T,7=F,8=T,9=T,10=F,11=T,12=T,13=T,14=T,15=F,16=T,17=T, 18=T,19=T, 20=T,21=T,22=T,23=T,24=T,25=F,26=T,27=T,28=T,29=T,30=T.

Total score=___.

This assessment is biased toward the ideal role of fatherhood. A score of 30 represents a very healthy and positive fatherhood. A score of 0 represents a very unhealthy and negative one. Can you identify the expressive and instrumental traits in your father figure? Many people make strong reference to their memories of their father figure when they themselves become adults and parents. How much of this process do you see in your own life? Prior to taking this assessment had your impression of your father figure changed significantly and if so, why? Has it changed after taking this assessment, if so why? Could you talk about this with him? Why or why not?

© 2014 Ron J. Hammond, All Rights ReservedMotherhood Patterns Assessment

This assessment is designed to explore your impression of motherhood. By answering the questions below, you will become familiar with the types of patterns exhibited in mothering behaviors, especially those you saw from your perspective as a child growing into adulthood. As you answer the T=True and F=False questions below, think about your own mother, stepmother, grandmother, or adult female (only one role if possible) who you would consider the primary mother figure in your growing up stage of life.

- T/F I could clearly tell when I had done wrong with her

- T/F The most common form of punishment was physical in nature

- T/F She would forgive my mistakes

- T/F She was never around to know if I was doing something I shouldn't do

- T/F She would forget about what I had done so I could move on

- T/F She punished me with reasonable punishments

- T/F At times, I really felt afraid of her

- T/F We always did things together

- T/F She was frequently at home in the evenings and/or weekends

- T/F She never really knew what I was going through

- T/F She knew who my friends were

- T/F She was a good provider for me

- T/F I felt protected by her

- T/F If people knew what I knew about her, they'd say she was a good mother

- T/F I couldn’t=t really talk to her

- T/F She was there to be a part of my life events

- T/F I was satisfied with her involvement with me

- T/F I could wake her up to talk if I needed to

- T/F She would take me shopping with her

- T/F She and I played regularly together

- T/F She touched me in ways I needed

- T/F She was cool around my friends

- T/F More than once, she pulled me out of a jam

- T/F She spent her money on me

- T/F I did not learn much from her

- T/F We worked together on things

- T/F We get along well now

- T/F When I was hurt, she took care of me

- T/F She=s the kind of person I=d Like to be

- T/F If I were like her, I=d make a good parent

Key=T,2=F,3=T,4=F,5=T,6=T,7=F,8=T,9=T,10=F,11=T,12=T,13=T,14=T,15=F,16=T,17=T, 18=T,19=T, 20=T,21=T,22=T,23=T,24=T,25=F,26=T,27=T,28=T,29=T,30=T.

Total score=___.

This assessment is biased toward the ideal role of motherhood. A score of 30 represents a very healthy and positive motherhood. A score of 0 represents a very unhealthy and negative one. Can you identify the expressive and instrumental traits in your mother figure? Many people make strong reference to their memories of their mother figure when they themselves become adults and parents. How much of this process do you see in your own life? Prior to taking this assessment had your impression of your mother figure changed significantly and if so, why? Has it changed after taking this assessment, if so why? Could you talk about this with her? Why or why not?

© 2014 Ron J. Hammond, All Rights ReservedProcessing the Fatherhood & Motherhood Patterns Assessments

Now that you have completed the Fatherhood and Motherhood Patterns assessments, you can study the influence these patterns might have or be having in your current roles and relationships. Answer the questions below and discuss them with your partner, parents, or a close friend. Keep in mind that the primary function of these assessments is to help you better understand your perspective and dispositions. It=s best to focus more on what you learn rather than how you might stack up in comparison to another person.

QUESTIONS:

1) Sometimes, in our parenting roles we act more like one parent than the other. Sometimes we act like a mixture of both parents. Which is the case for you? Why is it so?

2) What influence did your parents= other roles have on how they parented? For example sole versus dual breadwinners, traditional versus working-for-pay mothers, and any other significant adult-family roles.

Compare the father to the mother findings in the assessments (for questions 3, 4, & 5).

3) Who was the most expressive, nurturing, emotionally supportive, and connected with you?

4) Who was the most instrumental, providing, protecting, and economical sustaining for you?

5) Do you anticipate that you will be in similar roles with your partner when you parent?

6) How does your partner compare to the same sex parent you had?

7) How have past partners compared to the same sex parent you had?

8) Have you discovered any insightful trends or patterns that may be helpful to you in your perception of parent? If so, list them:

9) Why would or wouldn’t=t you talk to your parents about these findings? How does your answer impact your role as parent to your own children?

Additional Reading

Search the keywords and names in your Internet browser Children Bring Changes to a Relationship SOURCE

Parenting: Success Requires a Team Effort SOURCE

The Impact of Infants on Family Life SOURCE

Passion, Parenting & Keeping The Spark Alive SOURCE

United Nations on Children SOURCE

US Statistics on Children SOURCE

US Children’s Bureau Office of the Administration for Children & Families SOURCE

US Social Security Children’s Bureau SOURCE

Anne E Casey Foundation SOURCE

Annual Kids Count Data on US Children SOURCE